Claes Oldenburg, in full Claes Thure Oldenburg, (born Jan. 28, 1929, Stockholm, Sweden), Swedish-born American Pop-art sculptor, best known for his giant soft sculptures of everyday objects.

Much of Oldenburg’s early life was spent in the United States, Sweden, and Norway, a result of moves his father made as a Swedish consular official. He was educated at Yale University (1946–50), where writing was his main interest, and he worked from 1950 to 1952 as an apprentice reporter for the City News Bureau in Chicago. In 1952–54 he attended the school of the Art Institute of Chicago and in 1953 he opened a studio, doing freelance illustrating for magazines. Oldenburg also gained U.S. citizenship in 1953. In 1956 he moved to New York City, where he became fascinated with the elements of street life: store windows, graffiti, advertisements, and trash. An awareness of the sculptural possibilities of these objects led to a shift in interest from painting to sculpture. In 1960–61 he created The Store, a collection of painted plaster copies of food, clothing, jewelry, and other items. Renting an actual store, he stocked it with his constructions. In 1962 he began creating a series of happenings, i.e., experimental presentations involving sound, movement, objects, and people. For some of his happenings Oldenburg created giant objects made of cloth stuffed with paper or rags. In 1962 he exhibited a version of his store in which there were huge canvas-covered, foam-rubber sculptures of an ice-cream cone, a hamburger, and a slice of cake.

These interests led to the work for which Oldenburg is best known: soft sculptures. Like other artists of the Pop-art movement, he chose as his subjects the banal products of consumer life. He was careful, however, to choose objects with close human associations, such as bathtubs, typewriters, light switches, and electric fans. In addition, his use of soft, yielding vinyl gave the objects human, often sexual, overtones. Oldenburg’s Giant Soft Fan was installed in the U.S. Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, and his work was also exhibited at Expo 70 in Ōsaka, Japan.

Deeply inspired by Duchamp, Claes Oldenburg made radical contributions to sculpture. “I like to work with very simple ideas,” he once said, and while his ideas were simple, the results were groundbreaking. In rethinking scale, form and material as methods of disrupting the functionality of regular everyday objects, Oldenburg challenges us to reconsider our perceptions by way of his unconventional take through provoking our expectations of how ordinary objects “behave.”

In the early 1960’s the artist started to experiment with soft medium, defying the traditional rigid and static nature of the sculpture. With these works, Oldenburg proposed an alternate form, the “soft sculpture” which exists in a state of constant change. The “soft sculpture” has no fixed form, it is subjected to the forces of movement and gravity and configurations can be changed at any time. This innovative approach transformed the very definition of the sculpture.

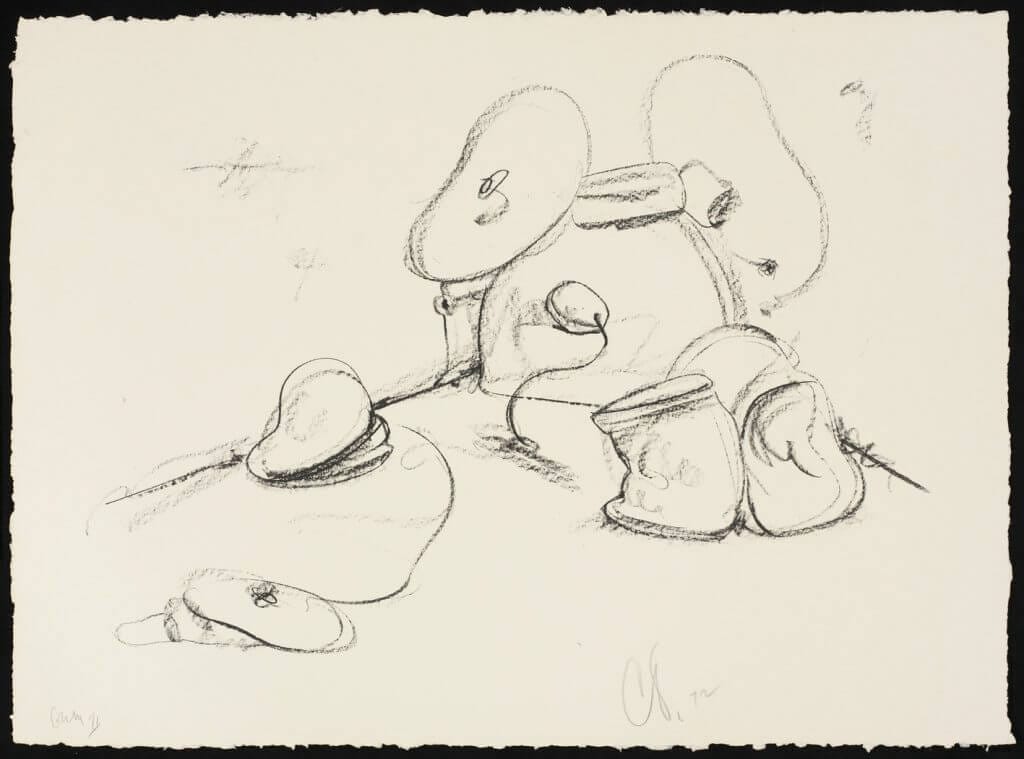

Oldenburg might be most famous for his monumental structures, however, he worked with scale in all capacities. The soft drum set was originally designed in 1967 as a large sculpture, inspired by the architecture of the Guggenheim Museum, but the small-scale model, created as the prototype for the project, became the basis for the miniature edition as well as a print edition done at Tyler Graphics studio..

Soft Drum Set, 1972

Lithograph

29 × 40 in

73.7 × 101.6 cm

Edition of 68

$ 3500.00

The notion of enlarging or diminishing everyday objects such as the drum set takes from the Surrealist movement and the concept of the absurd. In dramatically shifting the scale in his works, Oldenburg transforms the relationship between the viewer and the object through shrinking us or, in this case, enlarging us.

Nose Handkerchief, 1968

19-1/4 x 18-3/8 inches open

silk, screenprint

$2000.00

An exhibition of Oldenburg’s work in 1966 in New York City included, in addition to his soft sculptures, a series of drawings and watercolours that he called Colossal Monuments. His early monumental proposals remained unbuilt (such as the giant vacuum cleaner for the Battery in New York City, 1965; Bat Spinning at the Speed of Light for his alma mater, the Latin School of Chicago, 1967; and a colossal Windshield Wiper for Chicago’s Grant Park, 1967); but in 1969 his Lipstick (Ascending) on Caterpillar Tracks was placed surreptitously on the Yale University campus, remaining there until 1970, when it was removed to be rebuilt for its permanent home at Morse College, elsewhere on the campus. This began a series of successes, such as Clothespin (1976) in Philadelphia, Colossal Ashtray with Fagends at Pompidou Centre in Paris, and Batcolumn (1977), provided by the art-in-architecture program of the federal government for its Social Security Administration office building in Chicago.